What not-for-profit leaders need to know in 2026

Posted on 12 Feb 2026

Our special NFP trends report distils the views of more than two dozen experts.

Posted on 17 Jul 2025

By Paul Ronalds, founder and CEO of Save the Children Global Ventures, and former CEO of Save the Children Australia

Even before the covid-19 pandemic, it was clear the charity sector’s business model was broken.

Many charities were surviving only because of their historical investments in fundraising and financial reserves.

There are simply too many charities chasing too few dollars, all generally using the same business models in a sector experiencing declining fundraising returns at a time of escalating costs and demand.

New technologies, combined with limited progress on wicked problems and huge unmet need, means we need to seek new solutions to our greatest social and environmental challenges.

The pandemic accelerated these strategic challenges, leaving even less time for charities to get their houses in order.

Unfortunately, many charities, despite their innovative beginnings, have become radical ideas stuck in concrete.

I want to encourage charity management teams and boards to rediscover their courage to take bold decisions.

And philanthropists to re-think how they support the sector.

There are wonderful opportunities for us to leverage new sources of funding, new business models and new technologies to achieve a step change in our sector’s impact.

However, to take advantage of these opportunities will require us to much more clearly prioritise our mission over our organisations.

In some cases, this may mean a merger.

But let me begin by describing some conversations I’ve had with sector colleagues.

In one case, I was chatting to a colleague in another charity. We were discussing an opportunity to create an impact fund to invest in for-profit businesses aligned with the charity’s mission.

This charity had, through careful stewardship, accumulated a very large endowment fund.

When I suggested that the charity might like to use a small part of the endowment fund to establish an impact fund, my colleague said that was highly unlikely.

As the global pandemic took hold, another charity leader called me for some advice. She said that before the pandemic they had been struggling and the situation had now become dire.

We discussed their business model and potential sources of new funding but it seemed pretty clear to me that they faced some fundamental long-term challenges.

I suggested that she should consider a merger with one of the many organisations that had a similar mission, allowing them to reduce back-office costs and create cross-selling opportunities to generate new revenue.

She became defensive and indicated that a merger wasn’t "on the table”.

I have had the same reaction from many CEOs and directors when I have raised this issue, irrespective of the business case for a merger.

"In the for-purpose sector a merger is too often seen as a failure rather than as an opportunity to broaden reach, deepen expertise or increase policy influence with government."

These two examples involve very different organisations: one is very successful, in a strong financial position; the other is small and facing an existential crisis.

But in both cases, their leadership is confusing means with ends.

For-purpose organisations are created to achieve a social or environmental good.

Subject to your director duties, the merits of a decision should be determined by whether or not it advances the organisation’s mission, not the organisation.

The Australian branch of Save the Children was created in Australia over 100 years ago, just months after the organisation was founded in London.

Since then, it has grown to be one of Australia’s largest charities. And over that period, it has received billions of dollars in revenue. However, when I joined as CEO in 2013 it had very modest net assets, and for most of my tenure as CEO, we had negative free cash.

Successive boards and management teams had decided it was more important to use the organisation’s income to support the immediate health, education and protection needs of children than to build the organisation’s assets.

It’s hard to argue with that decision. Imagine explaining to a mother whose child needed life-saving help that you thought it was better to build an endowment for your organisation’s future.

Of course, it’s the role of directors and senior leaders to weigh up the immediate impact of expenditure against the potential for greater impact in the future.

And I will always be among the first to argue that many organisations have underinvested in building their back-office capability.

However, I suggest that too often the expected returns and risks of social investment decisions are not carefully enough calculated.

If boards and senior management were truly weighing up the strategic risks their organisations faced and the potential benefits to their mission, I think we would see leaders far more prepared to take on the difficult task of transformation.

And transformation is desperately needed. Take the aid and development sector, with which I am most familiar.

Over the past five years, the largest sector players have undertaken successive waves of restructuring, reducing head count by thousands. The most recent round has been in response to the dismantling of USAID by the Trump administration and massive aid cuts by European governments.

This rapid dismantling of global aid has been met with outrage from the aid and development sector. It hasn’t yet been met with enough introspection. Without a fundamental change to their underlying business model, aid and development organisations will be stuck in a never-ending cycle of cuts.

This reluctance to undertake more fundamental business model transformation is not limited to the aid and development sector. We have seen it in the disability sector in Australia, as a spate of NDIS providers have entered administration or liquidation or been forced to merge.

Many other NGOs – in Australia and globally – continue to face severe financial pressure, often in response to a dramatically changing strategic environment. They face a stark choice: as NGO consultant Barney Tallack put it, to transform, die well or die badly.

I want to spend some time looking at those three options.

First, transformation.

A few months after I was appointed CEO of Save the Children, the Abbott government was elected and immediately slashed overseas aid.

As the government’s largest NGO partner, Save the Children was hit hard.

Like Oxfam and World Vision, Save the Children was also experiencing falling private giving to international development, despite increasing investments in fundraising. And expectations of donors and regulators were rising, increasing costs.

It was very clear to me that if Save the Children was to fulfil our mission in this new strategic environment, we would need a dramatically different strategy.

We sought to significantly diversify our business model.

We expanded our work in Australia, especially in rural and remote Australia where our development approach was likely to be far more effective than traditional service delivery.

By 2021, we were working in over 200 locations in Australia, with 750 staff and a budget of more than $50 million.

We pursued accreditation with a number of global multilateral funds, and we became the first development agency in the world to be accredited by the Green Climate Fund.

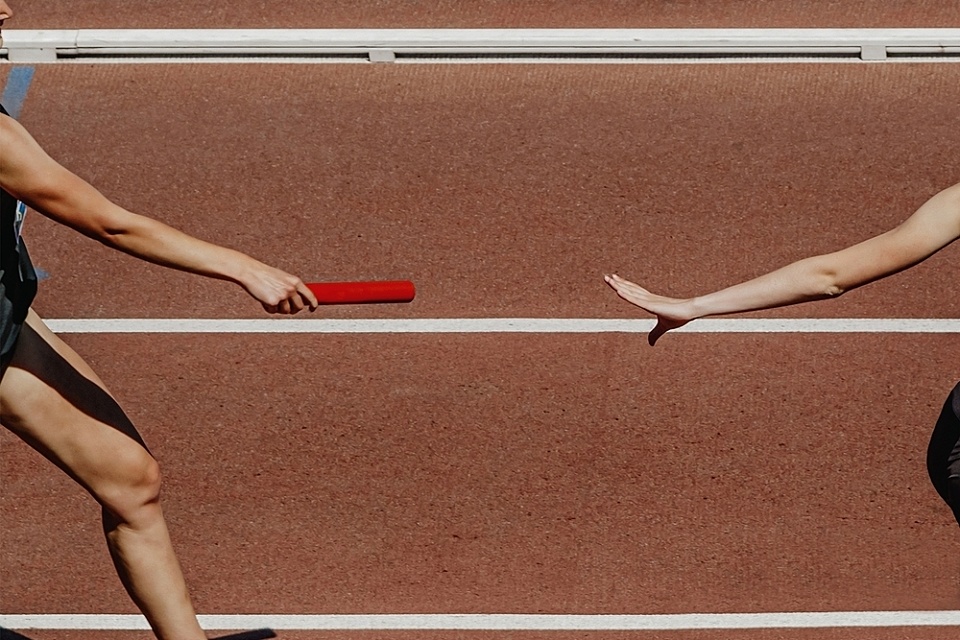

We invested time identifying merger opportunities where we thought one plus one could equal three.

We started new social enterprises like CEI (the Centre for Evidence and Implementation), which now employs people in Melbourne, Sydney, Singapore, Norway and London.

It’s undoubtedly the region’s leading evidence intermediary. More importantly, CEI is providing advice to governments that is having significant systemic impact on issues that go to the heart of Save the Children’s mission, like out-of-home care.

In 2020, we launched our first impact investment fund. The fund has invested its capital into a range of start-ups leveraging new technologies aligned with Save the Children’s mission.

One example is ATEC, which is at the forefront of decarbonising cooking in low-income countries, with plans to reduce carbon emissions by up to 10 million tons annually. ATEC's internet-of-things-enabled electric stoves offer particular benefits to women and children. By replacing traditional cooking methods, these stoves dramatically reduce indoor air pollution, which is a leading cause of respiratory diseases and premature deaths in children.

That first impact fund was the inspiration for Save the Children to create Save the Children Global Ventures, which I now lead.

Save the Children Global Ventures (SCGV) is Save the Children’s impact investing and innovative finance platform, established to mobilise high-impact capital to solve some of the most pressing problems facing children.

The success of the venture reinforced the urgent need for the sector to invest more in scaling up those interventions that are showing the greatest promise.

SCGV is focused on identifying new ventures that do this, providing capital and access to Save the Children’s global operations, networks and relationships in more than 100 countries to help them scale their impact and financial sustainability faster than they could by themselves.

New technologies provide enormous opportunities but it's an area where the charity sector seems a long way behind.

Covid demonstrated what was possible, triggering digital leaps forward that were expected to take years. The mass migration of workers to home that might normally be expected to take a year was done in weeks. Mobile money and digital payments soared as we stopped using cash. Global internet traffic increased by 70%.

Despite these examples. Despite the increasing pace of technological change. Despite covid. Despite all the challenges the charity sector faces, too many charity leaders still appear to act like our sector is somehow immune.

As a sector, if we are to reduce costs, we must extract greater efficiency from our back-office.

This will require investment in technologies such as artificial intelligence, which require new skills and capabilities; modern cloud-based finance and human resource systems; digital collaboration tools; and the latest office communication tools.

If we are to continue to receive support from the public, we must be able to engage with them seamlessly across multiple digital channels and technology platforms, all chosen by them.

This will require investment in new customer relationship management systems, mobile- enabled websites, and data warehouses.

And without modern back-office systems you are not going to have access to the data you need; or to be able to leverage front-line technologies that greatly enhance your impact.

These back-office technologies need to be seen by management, by the board and by supporters as critical enablers of your mission.

New technologies also provide opportunities to transform frontline service delivery.

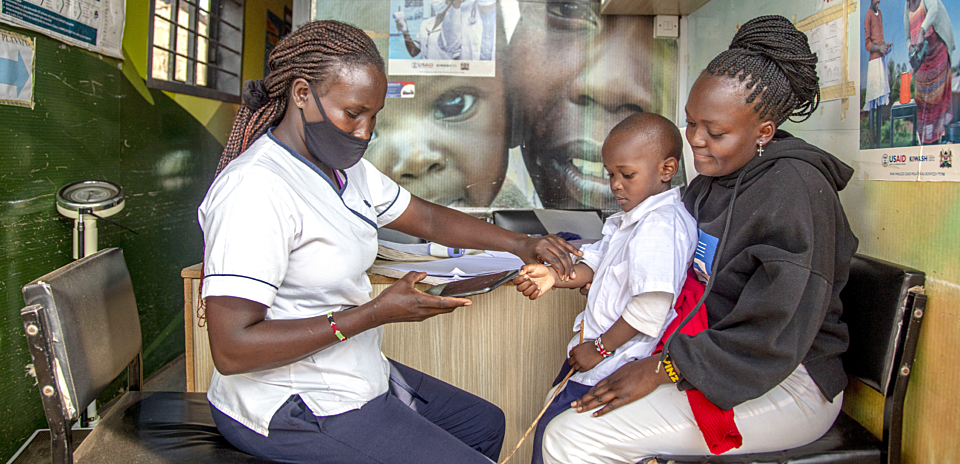

Ed tech, to combat school closures. E-health to provide high quality access to health services in rural and remote Australia. Fintech to more efficiently provide social protection programs in disasters.

Of course, we need to be careful of the gap between the prophesised potential and the real world results of many new technologies. New technologies are often overhyped. Many early initiatives fail to live up to their potential. We also know that new technologies can be used to do harm as well as do good.

We have seen far too many examples of some of our largest charities failing to protect supporter or beneficiary data from misuse.

Despite these challenges, charity leaders need to invest far more time understanding digital trends and their possible implications for the organisation’s mission.

We need charity boards to be spending more time interrogating management’s technology plans, to exploit new technologies as well as protect the organisation against its misuse.

And philanthropists need to stop viewing technology expenditure as administration to be minimised.

Returning to Save the Children’s transformation agenda, you can imagine that given our limited balance sheet and precarious cash position, this agenda required enormous courage from our board.

But when the pandemic hit and we were forced within days to all work from our home, Save the Children hardly missed a beat.

All our data was already in the cloud, able to be accessed securely from anywhere.

Fundraising was already leveraging new digital channels.

Through mergers and new social enterprises, we had access to ed tech solutions that hundreds of millions of children needed to continue their education from home.

Of course, we made mistakes along the way. Not every initiative we tried succeeded. But there is no doubt that the organisation’s impact for children is much greater now than before the pandemic.This is the true test of transformation success.

But I am the first to acknowledge that transformation is hard, for many reasons.

First, boards and executive teams have not focused enough on long-term strategic trends.

Second, despite the rhetoric about mission, most boards and management teams in practice prioritise the organisation over their mission.

This often happens because they lack the data and evidence they need to make better-informed decisions.

There has been too little investment in the evidence of impact.

Budgets for monitoring and evaluation are often significantly below what is required to produce reliable analysis.

When program evaluations do occur, they often focus on process, inputs or outputs, rather than outcomes.

These evaluations too often begin at the end of a program, rather than being planned during program design and integrated into the program logic and intended outcomes.

Evaluations are often of poor quality – because of a lack of independence, transparency and dissemination of results.

Third, there are insufficient incentives to make changes before value is destroyed.

Fourth, donors have starved charities of the capital they need. Donors want as much money as possible to be spent on direct program costs and see investments in organisational capacity as mere administration, to be minimised. This thinking is often encouraged by charities themselves.

Fifth, charities have systemically underinvested in IT for decades.

And sixth, they generally fail to create a continuous learning culture or invest in the professional development of their people.

If transformation is hard, dying well is too often seen as failure rather than success.

In the private sector, selling your business to a larger competitor is celebrated.

And it's often a great way for larger organisations to take great innovation to scale and rejuvenate their talent.

But in the for-purpose sector a merger is too often seen as a failure rather than as an opportunity to broaden reach, deepen expertise or increase policy influence with government.

Save the Children Australia has completed four mergers. They are difficult, but the returns to mission can be significant. There are several types of benefits:

Despite these benefits for the mission, most merger discussions founder not on lack of potential benefits but on concerns about brand, leadership and board positions and shared culture.

This means many charities are left to die badly, hoping that if they put off investments in new systems, delay staff salary increases or cut expenditure on professional development and training for another year, their prospects will somehow change.

They won’t.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution demonstrates it’s not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.

Unless charities face up to this evolutionary challenge and rethink the business of charity, they will fail the mission they seek to serve.

Ronalds was Save the Children Australia’s CEO for nine years, until June 2022. Save the Children Global Ventures aims to develop innovative finance and new technologies at scale, using Save the Children's global delivery platform with new funding mechanisms, ed tech, e-health and other technologies.

Posted on 12 Feb 2026

Our special NFP trends report distils the views of more than two dozen experts.

Posted on 10 Feb 2026

As my family dropped our teenage son off at the airport in the first week of January to embark on a…

Posted on 11 Dec 2025

Community Directors trainer Jon Staley knows from first-hand experience the cost of ignoring…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

As a qualified yoga instructor who learned the practice in her hometown of Mumbai, Ruhee Meghani…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Anyone working in an organisation knows it: meetings follow one after another at a frantic pace. On…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Stressed, overwhelmed, exhausted… if you’re on a not-for-profit board and these words sound…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

The Institute of Community Directors Australia trains over 22,000 people each year, which gives us…

Posted on 03 Dec 2025

Many not-for-profit (NFP) board members in Australia are burnt out, overwhelmed and considering…

Posted on 26 Nov 2025

A roll call of Victoria’s brightest future leaders has graduated from a testing and inspiring…

Posted on 12 Nov 2025

At the Institute of Community Directors Australia, we believe that stronger communities make a…

Posted on 12 Nov 2025

Like many Community Directors members, Hazel Westbury is a community leader who isn’t easily…

Posted on 11 Nov 2025

I’ve seen what happens when fear of conflict wins out over taking a principled stand.