Why women’s collective giving is a great growth opportunity in fundraising

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

Australia is entering the largest intergenerational wealth transfer in its history. Over the next…

Posted on 18 Jul 2023

By David Crosbie

In his first weekly column for the Community Advocate, the CEO of the Community Council for Australia, David Crosbie, ponders the merits of treating charities and NFPs as small businesses.

Charities are at the bottom of the organisational status listings in so many ways.

We talk about charities and not-for-profits (NFPs) as the third sector – behind business and government.

Charities are not seen as major contributors to our economy or our nation, even though they employ over 1.4 million Australians, turn over more than $190 billion annually and hold $422 billion in assets.

The value of charities is best measured not just in economic terms, but in the impact charities and NFPs have on our health, wellbeing, resilience and community connectedness. Unfortunately, these important outcomes of our work are rarely documented or valued in any meaningful way.

The skills required to successfully run a medium to large charity are broader and more complex than the skills required to run a business, not that you would know that from the conventional narrative in which successful business leadership is exulted, while leadership in the for-purpose sector is seen as softer and less demanding.

A major survey by Imagine Canada on the charity workforce this year found that charity employees tend to be better qualified and lower paid than their equivalents in business or government.

Money is an issue not only when it comes to salary levels. While most businesses have access to start-up loans and other favourable forms of debt financing, charities typically lack access to the capital they need and struggle to access any form of debt financing.

The devaluing of charities is not just in our workforce, our leadership, or our access to capital. It is also reflected in the way governments are structured and deal with charities and NFPs.

Short-term “take it or leave it” contracts, few of which factor in the true costs of providing services, have become standard government practice in their funding of charities and NFPs.

Governments sometimes refer to these arrangements as partnerships, but in most cases feudal lords had more equitable relationships with their serfs than governments have with their contracted charities and NFPs.

There are no government charity departments. The charity sector has no home in government, no set of dedicated officials working to increase its productivity and effectiveness.

The same cannot be said for small business or even the public sector itself.

Most industry groups of any size have dedicated public servants working to advance their competitiveness and profitability whether it be in agriculture, mining, or tourism or even information technology.

Government entities research their areas and provide support and information to enable the expansion of markets in Australia and around the world. Aside from the charity regulator – the ACNC – there are no senior public servants who see their role as championing the needs of charities in government.

The most important policy document a government prepares each year is its annual budget. Before the budget is locked away, treasurers and finance ministers across Australia will ask their senior officials to provide options to enhance and boost small business.

They know that any good budget needs to provide incentives to small business. Charity incentives are very rarely even raised as an option.

In practice, this means business can access many levels of government support that are simply unattainable for charities.

A small business concerned about cybersecurity can access government support to strengthen its safety. Charities cannot.

A small business can access training incentives in areas of skills shortage. A charity cannot.

A business investing in research and development and other forms of innovation can access targeted government grants and even rebates. A charity cannot.

A small business seeking to smooth out its energy transition from fossil fuels to renewables can access national government grants and loans schemes. A charity cannot.

Charities should not be the organisational child in the room, smiling graciously as the grown-up business and government sectors pat our heads and tells us what good boys and girls we are for helping.

Government-backed digital transformation and enhanced data security programs are available to support small business. Charities are ineligible for most of these schemes.

There are ad hoc government and philanthropic grant programs in some of these areas in some jurisdictions for some charities, but they tend to be highly competitive, short term and woefully inadequate for the scale of challenges thousands of charities are dealing with.

I have raised all these issues with government and been told that charities already enjoy income tax exemptions and most small business incentive programs are based on writing off income and tax liabilities.

As charities are generally tax exempt, to provide similar incentives would require actual grant programs, which are more difficult for government to approve because they involve additional expenditure rather than the foregone revenue of a tax write-off.

It is at this point that I find myself wondering: why be a charity?

Could we do the same work and achieve the same goals and purposes while operating as businesses?

Given that charities generally generate very low surpluses, most charities would be able to write off most of their expenditure and therefore not be liable for any tax (the same as many companies). So why bother being a charity?

The one thing we can say for sure is that as small businesses we would be taken more seriously by governments and politicians. We would be part of the “engine room of the Australian economy” and that would make what we want and need important to government.

For instance, I am pretty sure that if small business had to deal with the shambolic dog’s breakfast of Australian fundraising regulations that charities have to deal with, they would have been fixed by now.

I believe in charities, in the whole idea of collective action to drive change, to build flourishing communities and make a real difference in the world, not just contribute to an economy.

I don’t want to be a business, making profit for owners, but I do want to be taken seriously.

Charities should not be the organisational child in the room, smiling graciously as the grown-up business and government sectors pat our heads and tells us what good boys and girls we are for helping.

It’s time we stood up for ourselves. What does that mean?

I will explore this idea a little more in next week’s column.

David Crosbie has been CEO of the Community Council for Australia for the past decade and has spent more than a quarter of a century leading significant not-for-profit organisations including the Mental Health Council of Australia, the Alcohol and other Drugs Council of Australia, and Odyssey House Victoria.

He has served on numerous national advisory groups and boards including the first advisory board for the Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commission, the Not-for-Profit Sector Reform Council, and the National Compact Expert Advisory Group, which he chaired.

His diverse career outside the sector includes stints as a teacher in prison, a probation officer, a university lecturer, a farm hand, a truck driver, a bank teller, a public servant, and a musician in a successful rock band.

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

Australia is entering the largest intergenerational wealth transfer in its history. Over the next…

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

The founder and driving force behind the women’s philanthropic project She Gives, Melissa Smith,…

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

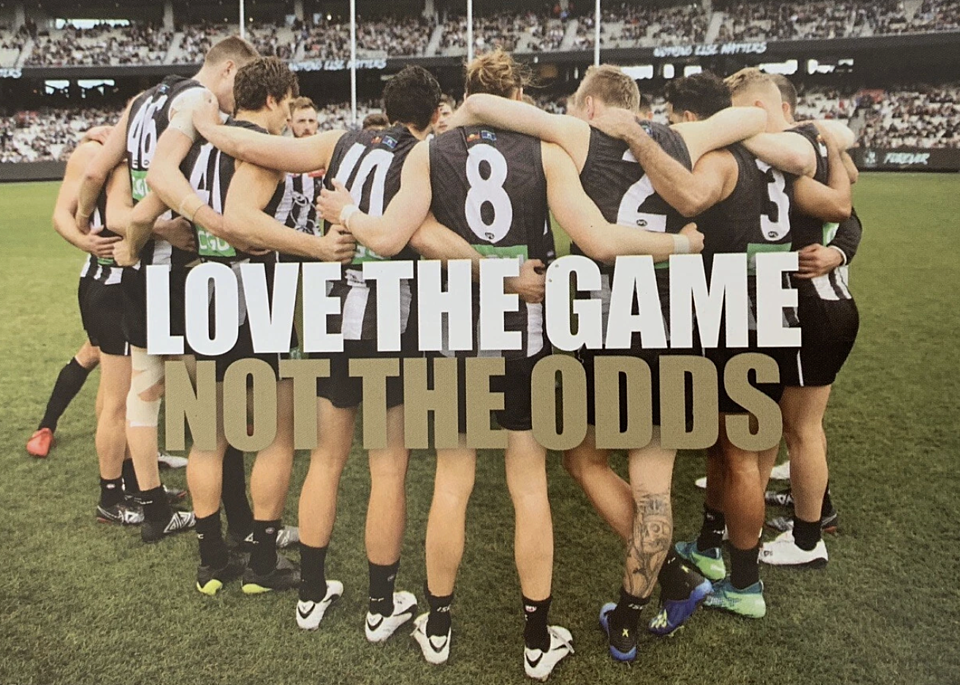

Footy is back, from rugby league in Las Vegas to Aussie Rules at the MCG, and you know what that…

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

Australia has offered asylum to members of the Iranian football team. That’s fine, but it does draw…

Posted on 11 Mar 2026

Applications are now open for the 2026 Joan Kirner Emerging Leaders Program, a fully funded…

Posted on 10 Mar 2026

Despite having a high-powered day job as a partner with Gilbert + Tobin, lawyer Catherine Kelso…

Posted on 10 Mar 2026

Australia’s future is being shaped right now in our migration and settlement systems. But too…

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

The federal government has announced its decision on the percentage of assets that giving funds…

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

Australia’s for-purpose enterprise supporting Indigenous-owned businesses announced a record $5.83…

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

Hannah Nichols is the environmental, social and governance (ESG) lead at Australian Red Cross and a…

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

Major workflow software company Atlassian has announced it is offering its Teamwork Collection of…

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

In all charities and NFPs – big and small – annual budgeting brings with it a degree of…