What not-for-profit leaders need to know in 2026

Posted on 12 Feb 2026

Our special NFP trends report distils the views of more than two dozen experts.

Posted on 13 Aug 2025

By Jenny Macklin with Joel Deane

Former federal deputy Labor leader Jenny Macklin knows what it takes to implement change, and the formation of the NDIS was one of the biggest reforms to affect the nation’s social sector in 40 years. Her recent book provides an inside look at how it was made possible. Here’s an extract.

How did the NDIS go from nothing to the biggest socio-economic reform of the past forty years?

The answer to that question is complicated; like so many other social policy reforms, it includes Brian Howe. In February 2008, shortly after the Apology, Brian requested a meeting with me and asked to bring along Bruce Bonyhady. Bruce, an economist who used to work in Treasury and sat on the Disability Housing Trust with Brian, was a disability advocate with the idea that, within five-and-a-half years, would become the NDIS.

I didn’t know any of this when Brian and Bruce walked into my office. All I knew was I trusted Brian and that trust enabled a good idea to germinate. At the meeting Brian told me a variation of the advice he’d already given Bruce: Australia was thinking about disability the wrong way. We needed to approach disability support as a form of insurance rather than welfare. He said disability should be seen as a risk issue because anyone could be born with or acquire a disability. The most logical response to that risk was to create a long-term social insurance scheme that covered disability.

Two central ideas emerged from that meeting. First, the community should take a lifelong approach to disability care and support; second, an insurance approach to lifelong care and support would allow the community to share the cost of the risk of disability. Those two ideas were soon joined by a third: disability support should be focused on the needs of the person with disability rather than the service provider. We had defined the policy problem. Now we needed to get the NDIS on the national agenda. This is where bloody-mindedness proved useful.

The 2020 Summit was held a month after my meeting with Bruce and Brian; however, with no one from the disability sector invited, there was no opportunity to introduce our ideas to the national thinktank. Bruce was undeterred. Working with philanthropist Helen Sykes, he co-authored Disability Reform, a document explaining the NDIS idea, then asked a Summit participant to smuggle their submission into one of the breakout sessions.

My friend and ministerial colleague Tanya Plibersek was in the Summit breakout session where Disability Reform was presented: ‘I thought it was a long shot. I actually thought, “Fantastic idea. I’m glad we’re talking about it. But this will be one of those things from the 2020 Summit that people say, Well, that’s too pie in the sky.”’

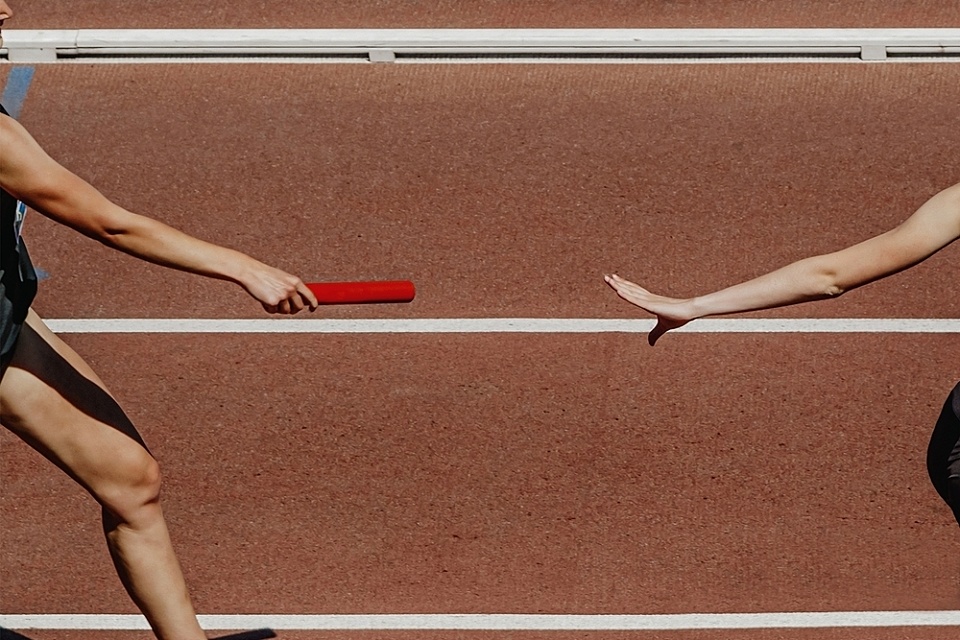

"Policy is a team sport."

Tanya was right. So, how did the Bonyhady-Sykes proposal manage to win support at the 2020 Summit? Again, the answer to that question is complicated, but the short answer is that the NDIS was an idea that knew its history. In 1973, the Whitlam Government initiated the Inquiry into Compensation and Rehabilitation, which recommended a no-fault scheme of accident compensation. The chair of that inquiry – New Zealand jurist Sir Owen Woodhouse – concluded that the most efficient, cost-effective way to handle accident compensation was to provide a national compensation scheme rather than focus on fault. Unfortunately, the no-fault scheme envisaged by Sir Owen was never implemented; the legislation was introduced to parliament just before the Dismissal in 1975. That meant anyone who acquired or was born with a disability continued to be treated as second-class citizens, remaining largely dependent on their friends and family because any state support they received was minimal and arbitrary. For instance, some states had no-fault transport accident insurance, but most didn’t, which meant people had to prove fault before they received any support. Medical negligence insurance was also fault-based, so only a fraction of the number of people injured were able to prove negligence and receive compensation. Workers’ compensation schemes, meanwhile, also varied from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Some states provided individual-funding support for people with disability, but those supports were narrowly framed.

As a result, thousands missed out.

The Bonyhady-Sykes proposal was informed by this history. They also knew disability activists had spent decades campaigning for greater individual control as well as the long-term shift from institutional to community-based care. In addition, they knew actuary John Walsh was leading excellent work on no-fault accident and catastrophic [injury] insurance in New South Wales. Bruce explains the approach he and Helen took:

‘Brian (Howe) gave me some people to talk to – none of whom had done anything in this area. And I found John Walsh and the work that he’d done on accident insurance. But John’s view was, “Let’s extend the existing accident compensation schemes from just medical injury and workplace and motor vehicle injury. Let’s make the default pay schemes for motor vehicles no-fault based. Let’s extend it out.”’

There’s another lesson here: policy is a team sport.

The development of the NDIS was a shared endeavour. Bruce workshopped the policy concept with Brian Howe and John Walsh, then worked with Bill Shorten and me in Canberra, together with state-level politicians such as the Bailleau Government’s Community Services Minister, Mary Wooldridge, in Victoria. Countless others also had a hand in the policy’s development, as well as the efforts to build the case for change.

One of the most prominent was Rhonda Galbally, the disability advocate who chaired the National People With Disabilities and Carer Council and, together with Bruce and others, led the creation of the National Disability and Carers Alliance that oversaw the running of the Every Australian Counts (EAC) campaign.

Other champions for the reform included John Della Bosca, the former Carr Government minister from New South Wales who became the first campaign director of EAC; Kirsten Deane, leader of the National Disability and Carers Alliance; and the hundreds of thousands of everyday Australians who, as a part of the EAC campaign, visited every politician’s office in the country to explain why the NDIS mattered to their families.

The release of Shut Out: The Experience of People with Disabilities and their Families in Australia was a major turning point in the campaign for the NDIS. There was an enormous amount of activity leading up to its release. Bill Shorten had set up the Disability Investment Group to consider how the NDIS might work, including eligibility requirements, levels of coverage, and models of operation.

There was a suggestion that the NDIS should only be an accident compensation scheme. I didn’t think that was equitable – hundreds of thousands of people with profound disabilities would have missed out. In the end, I decided the Scheme should be like Medicare – a social insurance scheme defined by need.

This was arguably the biggest decision I made in the development of the NDIS. It was a big call. I knew it had to be backed up by an authoritative piece of policy work with costings, otherwise it would never win the support of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Treasury, and Finance. I argued the case in Cabinet, which agreed to request a report from the Productivity Commission.

The Productivity Commission report had two main purposes: one, strengthen our understanding of the state of the disability sector; two, build the case for an unprecedented investment in the sector. The disability community weren’t so sure. They wanted greater control and didn’t want to leave their future in the hands of the Productivity Commission.

In the end, I convinced the leaders of the disability sector to back the Productivity Commission inquiry. The Productivity Commission softened any potential blow by establishing an advisory group, which included disability representatives, for its inquiry.

Next, as a part of the research for the development of the National Disability Strategy, Rhonda led the National People With Disabilities and Carer Council around the country, holding enormous town hall-style meetings with the disability community. The town hall meetings rallied the sector.

Australians from all walks of life came forward and told their stories about what life was like as a person with disability in Australia. Their stories were horrendous. Almost four-in-ten of the submissions received by the Council spoke of discrimination and human rights violations. Kirsten Deane still remembers the mood of those public meetings: ‘They were really raw. Really, really raw. Very emotional. There were tears, there was anger; they were electric.’

Rhonda’s Council gave their research findings to one of the big consultancies to write a report. The result, according to Kirsten, was underwhelming:

It was a bog-standard report … and everybody (on the Council) who’d been to these incredibly emotional, kind of town hall meetings were like, “Fuck that! That was not how people felt about it” … And, so, Rhonda (Galbally) basically dobbed me in. “Kirsten knows how to write. She can write it.”

I still remember receiving the report Kirsten wrote – Shut Out. It was not a typical Government document. It read more like a Royal Commission’s findings: raw and damning. It felt like we’d crossed the Rubicon. There was no turning back. Meanwhile, the Every Australian Counts campaign, which launched in 2011, kept up the pressure on federal, state, and territory governments. For Rhonda, a veteran of the disability rights movement, EAC was ‘terrific’:

It was a mobilizing approach. There were a lot rallies, that I’ve never seen before since going back to 1981, which was IYDP (the United Nations International Year of Disabled Persons) and the rally around deinstitutionalisation.

Tanya Plibersek thought it was the best community campaign she’d ever seen. I agree. Tanya’s take on EAC is insightful:

Ideas have a time. You can bring the time forward, you can delay the time, but ideas have a time. And I think the NDIS is one of many great examples of this … What brought the time of the NDIS forward into our term of government, I think, was the really good partnership between you, the disability advocates, and having someone like Bill (Shorten). I think that kind of combination of things meant that it was able to happen, perhaps sooner than it might otherwise have happened.

I think one of the real skills of people who are working outside government is to work out how they can create the environment where that idea can really take root and grow, where it can become inevitable that we’re going to do this, that this is something that needs to happen for the country. I think one of the best examples I’ve ever seen of that is the Every Australian Counts campaign, just making it a no brainer that we were going to do it and make it. Answering all the niggling questions that that people have about “How can we afford it? What’s the mechanism behind it?” …

In the implementation of complex social policy there is a conflict between urgency and patience and knowing when to be patient. And knowing when to put your foot down on implementation is really critical to success.

With the NDIS, I think we achieved almost the perfect balance between what Tanya calls urgency and patience. We defined the policy problem, we knew our policy history, we built the case for change and attracted public support, and, when the time came for implementation, we took our opportunity. Looking back, that process sounds preordained – even simple. It wasn’t.

This extract is reproduced from Jenny Macklin with Joel Dean, Making Progress: How Good Policy Happens, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, 2025.

Podcast: Jenny Macklin discusses the book with co-author Joel Deane

Podcast: Jenny Macklin talking about the book on Women’s Agenda iTunes | Spotify

Posted on 12 Feb 2026

Our special NFP trends report distils the views of more than two dozen experts.

Posted on 10 Feb 2026

As my family dropped our teenage son off at the airport in the first week of January to embark on a…

Posted on 11 Dec 2025

Community Directors trainer Jon Staley knows from first-hand experience the cost of ignoring…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

As a qualified yoga instructor who learned the practice in her hometown of Mumbai, Ruhee Meghani…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Anyone working in an organisation knows it: meetings follow one after another at a frantic pace. On…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Stressed, overwhelmed, exhausted… if you’re on a not-for-profit board and these words sound…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

The Institute of Community Directors Australia trains over 22,000 people each year, which gives us…

Posted on 03 Dec 2025

Many not-for-profit (NFP) board members in Australia are burnt out, overwhelmed and considering…

Posted on 26 Nov 2025

A roll call of Victoria’s brightest future leaders has graduated from a testing and inspiring…

Posted on 12 Nov 2025

At the Institute of Community Directors Australia, we believe that stronger communities make a…

Posted on 12 Nov 2025

Like many Community Directors members, Hazel Westbury is a community leader who isn’t easily…

Posted on 11 Nov 2025

I’ve seen what happens when fear of conflict wins out over taking a principled stand.