The king of literary silliness becomes Australia’s Children’s Laureate

Posted on 25 Feb 2026

Author Andy Griffiths has spent 30 years bringing “punk rock” to children’s books, making kids…

Posted on 11 Feb 2026

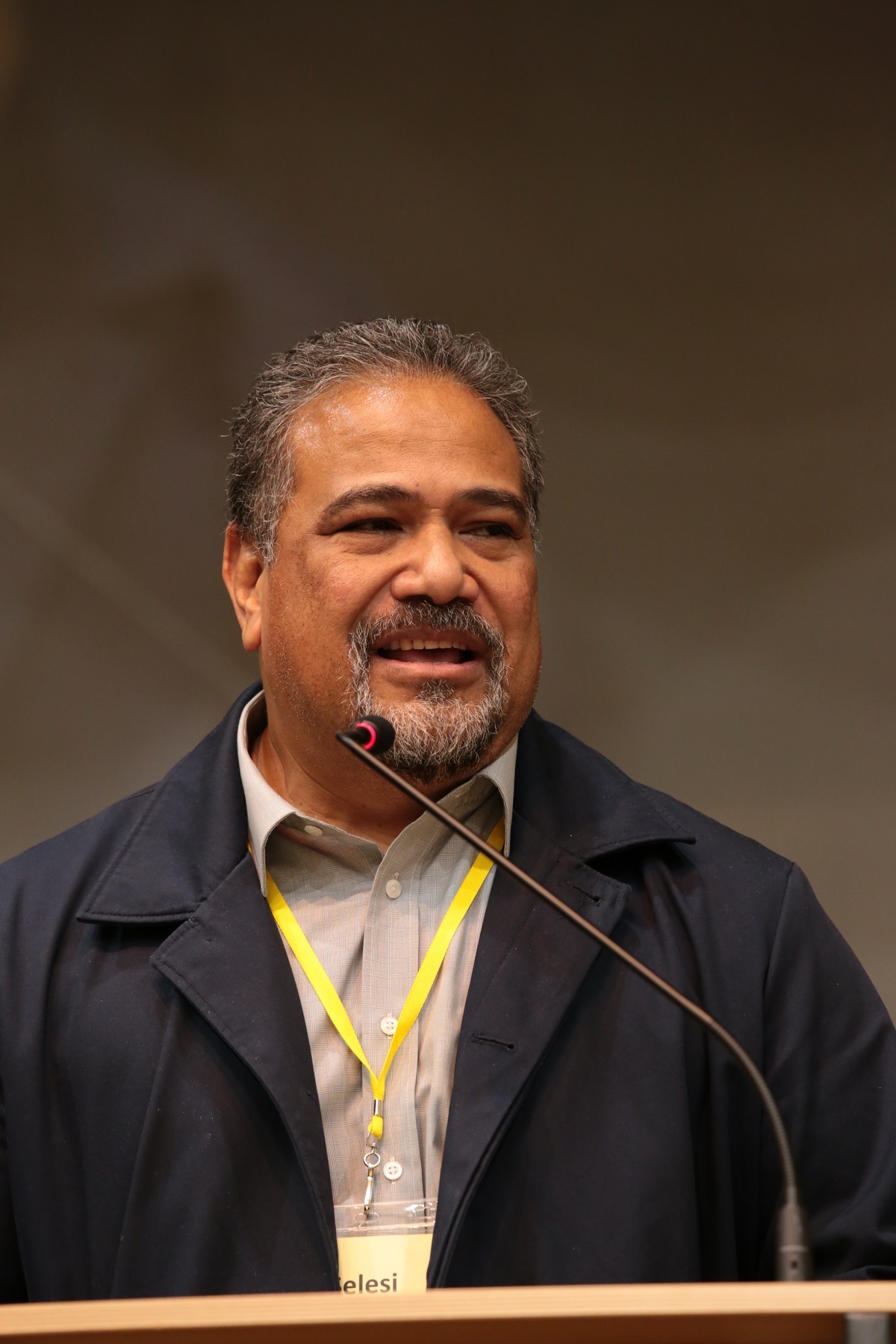

By Nick Place, journalist, Community Directors

Rev. Salesi Faupula is the Uniting Church’s moderator for the synod of Victoria and Tasmania. Born in Tonga, and a motor mechanic for many years, he has found that his unusual backstory helps his work. We spoke to him about what he does.

It’s part of the cog within the synod processes and governance structure. It almost sits alongside a bishop, in the Anglican or Catholic church, but without the same powers that a bishop would have within that structure. We don’t see the role in terms of value and power. The synod has a number of committees, and a standing committee for decision making and oversight.

The moderator’s role is to chair those meetings.

In my 20 years in congregational ministry, I’ve participated in committees within the presbytery, the synod and the assembly, so there have been bits and pieces that I have been involved in in the past, but this is quite a unique positioning, to get a broader view of the church. Given the role’s connection with its presbyteries and ultimately serving congregations, it’s not so much an authority position. It’s viewed still very much in a servant capacity.

There are challenges, and I think that’s normal. We use the metaphor of a pilgrim people. We are a church that continues to be guided by our discernment in our faithfulness to the gospel, which is our faith in God, and that has a movement to it. There’s a movement of both aspirational and faithfulness, to the call, and so the direction is both in concern of proclaiming the gospel, but also attentive to the community and the way in which we move together as a body.

I really had other plans, early on, and, in fact, was a motor mechanic for 16 years before I decided to answer my call. My father came over as a Methodist missionary in 1972, but the Uniting Church formed in 1977, so I’ve really only known the Uniting Church all my life. My father was a minister. My grandfather was a minister. I’m actually at least sixth generation in my family of being a minister.

So, being in the church didn’t necessarily appeal; I viewed that as my father’s domain, plus there was a kind of a growing struggle with my own identity outside of that. I was only three months old when we came to the very tip of Arnhem Land in Gove, and we were in the Northern Territory for 10 years, until 1982. My father’s placement was coming up, and there was a growing Tongan community in the Northern Beaches in Sydney and so we ended up moving to Dee Why.

When we moved to the Northern Beaches, I remember the perception there of the Indigenous people, First Peoples, was quite negative. I had grown up in the Territory, but then as I grew up on the Northern Beaches, I distanced myself from my Aboriginal upbringing. I could speak the dialect of the tribe, but I lost that as I distanced myself, and I became more and more, I think, unsettled in terms of who I was, and so I didn’t want to be known or connected to the Northern Territory. [Salesi has recently reconnected with the community there.]

My brother and sister and I were the only brown kids at school, and so I realised that I wasn’t white by my skin colour, and I decided that I’d be Tongan, and that would be my identity, but it was the least culture I knew, even though I was born there, and the only parts of Tongan that I understood was what was at home, and then the growing community that was around us.

I asked my father to send me to Tonga and he did, to a boarding school, when I was 15. I got off the plane and I couldn’t speak the language, so in this place that was supposed to make sense, I was in the margins yet again. I immersed myself to learn the language and embraced my Tongan-ness, as well as my Australian upbringing. I think in English, and some of my behaviours are very much middle class suburban Australia, but I am also working to reclaim and value my Indigenous upbringing.

These days, I have defined myself as a “colourful mess”.

When I think about who I am, in terms of my identity, if I named one, I’d be denying the other two, so the only way that I can feel that everything is represented is this colourful mess.

“My father taught me what was meaningful and purposeful in a life was a life of service, and he always used to emphasise this service to others.”

Yes. Those tensions within my own identity of different cultures – and also the joys from within it – mean I find that it’s helped me maybe listen a little bit deeper and to seek out ways in which we can journey together. There’s this inclusive understanding, the complexities of diversity, but unifying behind a common good, within the Uniting Church, that I’ve really connected to individually.

My father taught me that what was meaningful and purposeful in a life was a life of service, and he always used to emphasise this service to others – even down to my years as a motor mechanic, because he said our family didn’t have any mechanics. I remember looking at the office of my first placement, and it was a beautiful office, and all I could think was that its beauty would match the responsibility that comes with being in such a beautiful office. My upbringing told me that there was a responsibility to those things, instead of considering it in terms of privilege.

I’m compelled not only by my own faith, but this genuine love for humanity to stand and believe that peace is still possible. I’m drawn by the story and the gospel in the New Testament of the disciples and Jesus in the boat when they’re in the storm and the disciples are frightened. The wisdom of that story, to me, is that it says you don’t fully understand what peace is until you’ve experienced the depths of tragedies.

Right now, storms are happening and it doesn’t mean we don’t respond to them. It does mean that we stand upon a common good, and we are careful because the nuances are unique to that situation. I believe that we need to spend real time in the storm, to be able to offer the peace that’s actually going to last. It’s not one size fits all. Not one storm is explained. Not one group explains the whole group. And that’s the challenge.

There is this kind of growing voice that’s simmering back here in Australia – racism, discrimination, Australia Day – and how do we engage with that honestly? It’s almost like you need to be on one or the other.

The “colourful mess” that I come from says there’s a tension in the middle, and people say, “Oh no, you can’t be just sitting on the fence.” It’s not sitting on the fence, it’s actually being in the storm that defines the strength of it, so that instead of being polarised either this way or that, the tension that lies in the middle is perhaps where the grace and the peace reside. It’s that wrestling within that storm that builds the resilience or our humanity to see beyond just the classifications that we have.

Posted on 25 Feb 2026

Author Andy Griffiths has spent 30 years bringing “punk rock” to children’s books, making kids…

Posted on 18 Feb 2026

When Nyiyaparli woman Jahna Cedar travels to New York next month as part of the Australian…

Posted on 11 Feb 2026

Rev. Salesi Faupula is the Uniting Church’s moderator for the synod of Victoria and Tasmania. Born…

Posted on 04 Feb 2026

At the Third Sector leadership conference in Sydney last year, Queensland health executive Chloe…

Posted on 28 Jan 2026

French-Canadian Jimmy Pelletier, who lives with paraplegia, is six and a half months into a…

Posted on 16 Dec 2025

Lex Lynch spent more than two decades in the climate change and renewables field before last year…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

A long-time advocate for rough sleepers in northern New South Wales has been named her state’s…

Posted on 03 Dec 2025

Emma-Kate Rose is the co-CEO of Food Connect Foundation, working with communities to support the…

Posted on 26 Nov 2025

Next Wednesday, December 3, All Abilities ambassador Greg Pinson will be celebrating the…

Posted on 19 Nov 2025

Lora Inak is the author of the Cockatoo Crew books, a new children’s fiction series (illustrated by…

Posted on 11 Nov 2025

Project Manta, a long-running scientific study that includes a citizen scientist component, is…

Posted on 04 Nov 2025

Diamando Koutsellis is the CEO of the not-for-profit Australian Ceramics Association, as well as a…