How to make repairs when the world seems to be coming apart at the seams

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

Hannah Nichols is the environmental, social and governance (ESG) lead at Australian Red Cross and a…

Posted on 11 Nov 2025

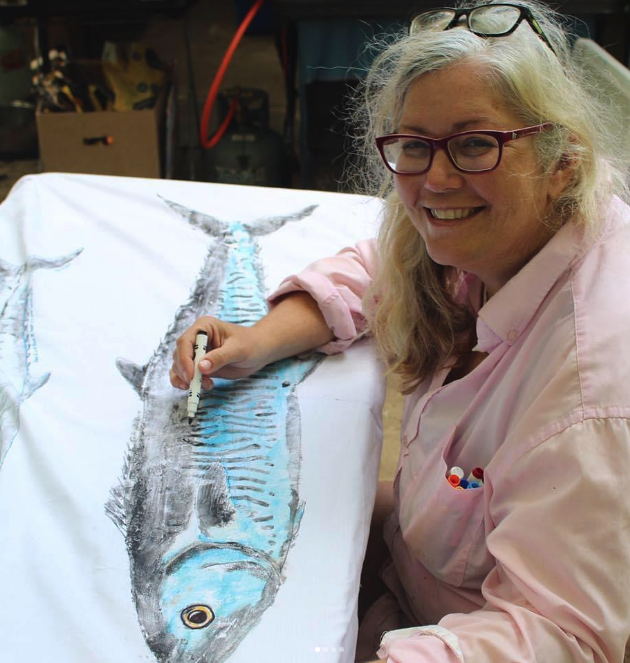

By Nick Place, journalist, Community Directors

Project Manta, a long-running scientific study that includes a citizen scientist component, is about to be incorporated into a brand-new not-for-profit organisation, the Manta Foundation. The project’s founder, Associate Professor Kathy Townsend, a Canadian-born marine scientist, explains why she still gets excited every time she swims with giant mantas.

Being in the water with the manta rays. Well, just being in the water, full stop. I mean, I’m equally as excited and curious about manta rays as I am the plankton and tiny little fish and everything else. It’s just being in the water and exploring this amazing, really foreign environment where most animal creatures live. When I was young, space was a really big thing, right? Everybody wanted to go to space, but I very quickly realised that if you go to space, you’re just going to see rocks. But if you go under the water, you’re going to see the most outstanding aliens you could possibly imagine in all shapes and forms that you wouldn’t see in space. So to me, it’s even better than being in outer space. I love it.

I always consider manta rays to be like the ocean’s canaries in the coalmine. They’re a big-bodied animal that we can quite easily study, but they feed on the smallest things in the ocean: plankton. We know that plankton is very readily impacted by climate change, by changes in water temperature, changes in the strength of currents; all those things very quickly and readily impact the plankton. So if the mantas are changing their behaviour, changing where they’re going, when they’re going, that can give us some of these early warning signs of things that might be happening to plankton and the wider health of the ocean. Also, if the mantas themselves start to show poor health, that’s another indicator that something will be happening, and studying things like seasonality, how their migrations north to south might be impacted by water temperatures at the time, if we start to see that the animals are arriving sooner or leaving later or vice versa.

That’s from the ecosystem perspective, but another reason to be studying manta rays is that they’re a large charismatic animal that people can have really meaningful interactions with. Mantas come and check you out, and there are not very many particularly big wild species that will do that. It’s a big opportunity, almost like a gateway drug, of getting people to care about the environment, because when they have a personal experience with the mantas, they start to ask more questions and be concerned about the animals being able to live into the future. It’s a little bit like the panda from the WWF. You think of the panda, cute and cuddly, but WWF is not just about saving the panda; it’s about saving the habitat of the panda. If their mascot was bamboo, I don't know if they’d get quite the amount of buy-in.

If you look around Australia, it’s more than 3500. On the east coast, I think we’re up to 1800. And we’ve got these fantastic stories ... we’ve got the world’s only pink manta, “Inspector Clouseau”, and we’ve got the oldest known manta, “Taurus”, who is over 55 years old – he’s possibly coming up to 60 years old – and he’s still hanging around Lady Elliot Island, still flirting with the girls, so he’s still doing his thing. We’ve got two immature males that had been seen down at South Solitary Islands, New South Wales, and then they were both seen at the SS Yongala, off of Townsville. That’s well over 1,000 kilometres in a straight line, and prior to that, the longest distance that this particular species of manta had ever been known to go was about 350 ks. So we’re now the world record holders for the distance for that species.

At the moment, we’re working with a Japanese aquarium, who are coming back next year for a second visit to perform ultrasounds with a wand passed across the back of the animals, on wild, free-swimming mantas, to see if females are pregnant or at what stage the males are at, as far as their testicles are concerned.

But we don’t know everything. We still don’t know where the manta babies are, we don’t know where the pupping grounds are, where the female mantas give birth.

“I very quickly realised that if you go to space, you’re just going to see rocks. But if you go under the water, you’re going to see the most outstanding aliens you could possibly imagine in all shapes and forms.”

It’s about being able to maintain the work into the future. I always joke, although it’s not a joke, that I have a folder that lives on my desktop called ‘Save Project Manta’, and I need to open it every three years, at every funding round. Next year is Project Manta’s 20th anniversary, so I don’t know how I’ve been successful in keeping this thing going for 20 years, often on the sniff of an oily rag.

It’s really come about because of Josh Heller, who’s from Sydney and has been the driving force, after being introduced to us by Dr Guy Stevens from the Manta Trust, which is UK based. It’s something I have wanted to do for a long time, but just one of those things I didn’t have the space, the capacity or the expertise. Josh was able to connect us with lawyers who do social justice work every year and took it on. They organised all the paperwork, everything that needed to be done to turn us into an NGO, and it’s a massive relief. We’re at the very early stages, still haven’t officially launched, but it’s happening.

Initially, it’s for us to get traction and get word out there about what we’re going to be doing, which is, to start with, concentrating on funding research that’s being done in Australia. At the moment, that’s mostly Project Manta, but we do have ambitions, as it hopefully gets bigger and expands, that we end up being able to help in our Pacific region as well. We’ve already got connections to Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Fiji, for example, so some of those places in our region that could potentially do with a hand for mantas as well, that’s what we’re hoping to do. That's not going to be in the first year or so.

A big part of Project Manta has always been the citizen science component, and the community outreach. [Project Manta asks the public to submit photos of the underbelly of manta rays they see while snorkelling or diving, as every manta’s belly has a different pattern, like a fingerprint, allowing identification.] If you haven’t got someone there to monitor when people send images, and give them feedback, as in who this animal is, it drops off quickly. We promise we’ll tell people sending photos who the animal is, and where it was last seen, or if it’s a new manta, they get to name it. But you need the people to [manage the process].

The charity is about us thinking long and hard about how do we sustainably maintain Project Manta going forward into the future? How do we continue this long-term monitoring and long-term citizen science project into the future? In particular, paying for the personnel that we require to be able to do that? Doing the science, if we’ve got a specific research project, around reproduction or something, we can apply for a short-term grant to be able to do it. But most of these grants will not give us money for people, and for most of us who work in science, that’s the problem, in that there's very rarely money for people.

No, I didn’t, but I was involved, being interviewed for the script. I got to see the final script, and it was, like “Attenborough, Townsend, Attenborough, Townsend”, and I’m, like, oh my God! Peter Gash, who runs Lady Elliot Island Eco Resort, went to the official opening in London and spoke to Sir David, who said the manta section was his favourite part of the entire documentary.

The Manta Foundation website is under construction.

Kathy's art: Instagram: @science_loves_art

Posted on 04 Mar 2026

Hannah Nichols is the environmental, social and governance (ESG) lead at Australian Red Cross and a…

Posted on 25 Feb 2026

Author Andy Griffiths has spent 30 years bringing “punk rock” to children’s books, making kids…

Posted on 18 Feb 2026

When Nyiyaparli woman Jahna Cedar travels to New York next month as part of the Australian…

Posted on 11 Feb 2026

Rev. Salesi Faupula is the Uniting Church’s moderator for the synod of Victoria and Tasmania. Born…

Posted on 04 Feb 2026

At the Third Sector leadership conference in Sydney last year, Queensland health executive Chloe…

Posted on 28 Jan 2026

French-Canadian Jimmy Pelletier, who lives with paraplegia, is six and a half months into a…

Posted on 16 Dec 2025

Lex Lynch spent more than two decades in the climate change and renewables field before last year…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

A long-time advocate for rough sleepers in northern New South Wales has been named her state’s…

Posted on 03 Dec 2025

Emma-Kate Rose is the co-CEO of Food Connect Foundation, working with communities to support the…

Posted on 26 Nov 2025

Next Wednesday, December 3, All Abilities ambassador Greg Pinson will be celebrating the…

Posted on 19 Nov 2025

Lora Inak is the author of the Cockatoo Crew books, a new children’s fiction series (illustrated by…

Posted on 11 Nov 2025

Project Manta, a long-running scientific study that includes a citizen scientist component, is…